We are living through interesting times. There is a new UK government, promising an enduring partnership with business to deliver the economic growth we need.

This sounds very exciting, except it comes with rumours of impending capital gains (CGT) and inheritance tax (IHT) increases in the upcoming Budget, likely to achieve exactly the opposite.

These tax areas present real disincentives to investment in innovative enterprises, which might otherwise generate that heralded economic growth.

Any continuing meddling with CGT following the virtual destruction of personal annual allowances by former chancellor Jeremy Hunt last year will be challenging for those of us in the investment business.

Gains indexation allowance was removed in 2008, introducing a direct taxation on inflationary ‘non-gains’. In the meantime, personal annual CGT allowances (the annual exempt amount) have been consistently reduced from £12,300 as recently as 2023, to a mere £3,000 currently.

That is quite a big ask for an investment manager and the risk of getting it wrong is suddenly multiplied

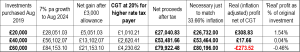

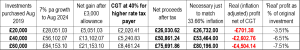

This means an investor who bought shares worth £20,000 some five years ago (August 2019) and has just sold them in August 2024 for £28,051 (based on five years’ reasonable theoretical annual returns of 7%) would be in line today, beyond their annual CGT allowance of £3,000, to pay either £505 or £1,010 in CGT (at 10% or 20% depending on whether they were a standard rate or higher rate income tax payers).

Based on actual government recorded inflation of 33.66% over those years, their investment would need to equal £26,732 to have retained its purchasing power.

If, as seems likely in most cases, they are higher rate taxpayers, they would have net proceeds of £27,041 after CGT – a paltry ‘real’ inflation-adjusted return of 1.54% over the full five-year period.

It gets worse the more that is invested…

Moreover, the impact of any increase in the rate of this tax, which was already a tax largely on inflation and therefore doubly unwelcome, would make active portfolio management even more challenging than it is today.

Who but the bravest manager is going to sell an asset with a gain, paying up to 40% tax on virtually all, if not all, of that gain, to reinvest with the intention of building on that (now net) gain in a compelling replacement asset?

The justification for doing so could only be to recoup at least that ‘surrendered’ gains tax, before then seeking further actual gains within the replacement asset.

That is quite a big ask for an investment manager and the risk of getting it wrong is suddenly multiplied – by personal CGT allowances having been dropped to insignificant levels but also now the added risk of a higher tax rate, allegedly potentially, doubling (see table below).

On an inflation-adjusted basis, the outcome looks dire. But there is one way to try to mitigate these changes.

It involves converting actively managed individual portfolios (or even the most gently managed portfolios) into holdings in virtually identical portfolios but managed for groups of similar investors in portfolio-style collective funds – where, crucially, underlying trading is then exempt from CGT.

Portfolios can continue to grow, profit on profit, CGT free, via active management, so gains only come into play once when each investor finally cashes in any units/shares from the collective version of their portfolio.

Taking one final, across the board, potential CGT hit to initiate portfolio-style funds would create clean ‘portfolios’ for each investor going forwards.

Portfolio managers currently using model portfolios should consider moving clients into their own branded portfolio-style funds on a collective basis for groups of clients with similar investment requirements.

Alison Dean is head of investment oversight at Way Fund Managers

Comments