Government bonds underperformed other asset classes last year, posting a negative return versus another double-digit year for equity markets, rising property prices and strength in commodities.

The negative trend has continued into the new year, with US 10-year yields up 1.2% in the last four months and UK yields at their highest level since the 2008 financial crisis.

It’s unusual for bond yields to rise when central banks are cutting rates. Many commentators attribute higher gilt yields to politics, pointing to the recent Budget, but it’s a global phenomenon.

We see an economic justification. Stronger-than-expected global growth and higher-than-expected inflation means fewer rate cuts. Against this backdrop, we continue to prefer stocks to bonds.

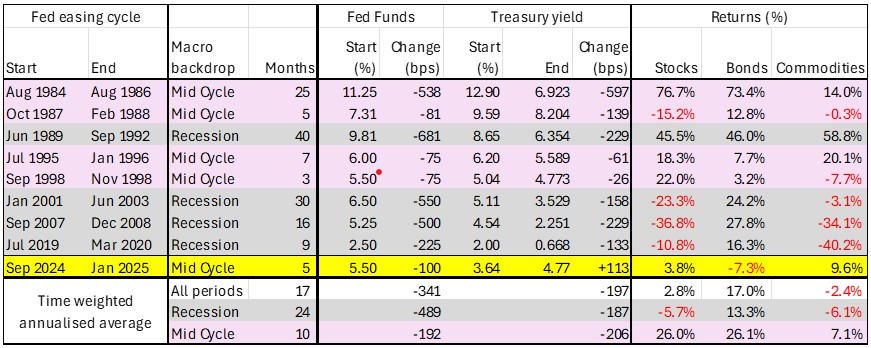

The US Federal Reserve joined a multitude of other central banks joining in. On about half of the occasions, the beginning of a rate-cutting cycle has coincided with weakness in the economy and recession – accompanied, understandably, by weakness in stocks.

Many commentators attribute higher gilt yields to politics, pointing to the recent Budget, but it’s a global phenomenon

On other occasions, rates came down on the back of a fall in inflation. In these ‘soft landings’, equity markets rallied. In all eight of the previous instances, one thing has been consistent: rate-cutting cycles have always been positive for government bonds (Figure 1).

Until now. The Fed has cut rates by a full percentage point since September, but government bonds have sold off aggressively, with 10-year Treasury yields and gilt yields rising by around 1%.

We think this move in bond yields is due to the major wrong-footing financial markets have suffered since the summer. Back then, investors were in fear of an imminent recession on the back of a gradual rise in the US unemployment rate and markets were pricing in 10 quarter-point Fed rate cuts.

We’ve seen four cuts, but the US economy has proved much more resilient than expected and deregulation from an incoming Trump administration could add fuel to the recovery. Markets now expect only one or two more cuts.

Figure 1: Financial market behaviour during Federal Reserve easing cycles

Source: RLAM. Changes between first and last Fed rate cuts. Total returns in US dollars using S&P Composite index for stocks, 10-year US Treasuries for bonds and the GSCI index for commodities. Current instance as of 10 January 2025.

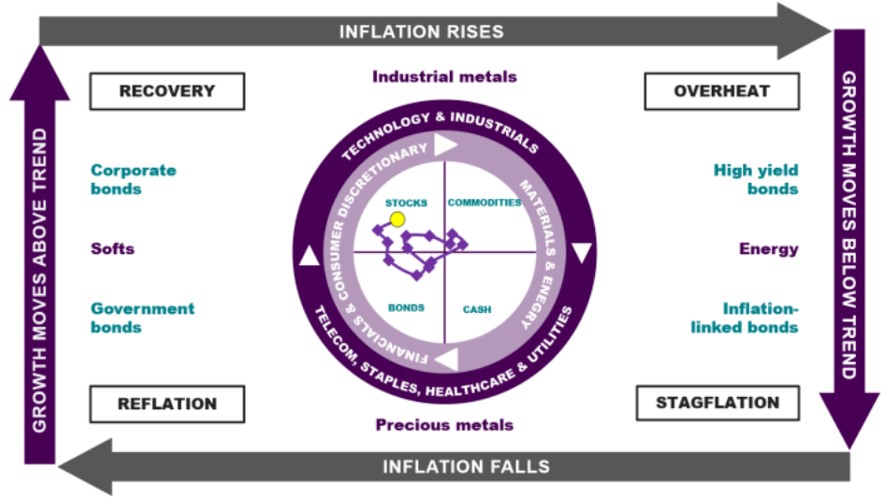

There is further upside risk to bond yields from here. The Investment Clock model that guides our asset allocation is in the equity-friendly Recovery phase (Figure 2). We draw similarities between this period and the 1998/9 experience, which saw rate cuts quickly turn into hikes.

In this scenario, as in 1999, strong earnings growth would probably still see stocks beating bonds – at least until higher interest rates took effect.

Figure 2: The Investment Clock is in reflation but moving towards overheat

Source: RLAM. For illustrative purposes. The trail and yellow dot signify the momentum of global growth and inflation based on RLAM’s proprietary scorecard indicators over the last 12 months.

However, the incoming presidency of Donald Trump presents one additional layer of uncertainty, which could easily change outlook on inflation and growth. Tariff increases and the deportation of undocumented migrants could dent US growth, raise prices and derail a fragile global recovery.

As active investors, we need to take one step at a time. For now, we see the rationale for higher bond yields, but we stand ready to sell stocks and buy bonds if the world economy takes a turn for the worse.

At these higher yields, government bonds are once again ready to perform a shock-absorber role for portfolios in case of economic weakness.

Trevor Greetham is head of multi-asset at Royal London Asset Management

An interesting if somewhat rose tinted, in my opinion, view of the next 12 months…

Two points I would make –

1. The Fed cares nothing for stocks but IS obsessed with inflation and keeping interest rates aligned based upon that predication – less cutting so higher bond yields;

2. UK is decoupling itself, to the extent it can, from the US probably at a near record pace… consider… recent NI measures, tax gathering, employment protection measures, the ever present ‘disco biscuit’ green tripe – this is almost the opposite of what is happening compared to the (new) US paradigm.

Added to this, BoE is sucking £100Bn of private money OUT of the economy this year as it reverses QE – hardly of any assistance to the growth crusade!! These are bonds already issued, thus, leaving less for new Gilt sales – yields go up…

The good news is that Trump has included oil and gas in the ‘trade imbalance’ tariff rhetoric, looks like, as we take another opposite to’drill, baby drill’, we will have a secure and friendly source of energy to import from.

Maybe we should ‘sell’ our trade deficit with US to others – Germany – like a carbon exchange… non?