In everyday language, being ‘independent’ is a positive thing. People who are described as independent are self-sufficient and self-confident; they know their own mind. An independent tribunal or inquiry is one where we expect a fair and impartial hearing.

Independence is even at the heart of the UK constitution, through the separation of the executive, legislative and judicial powers of the state.

In financial services, however, independence has a specific regulatory meaning that developed in response to various financial scandals of the early 1980s.

Not all people who say they are independent are in fact independent

Today’s independent financial adviser — as set out in the FCA Handbook — must look at a sufficiently diverse range of relevant products to ensure a client’s investment objectives can be suitably met. IFAs cannot limit themselves to in-house products or those offered by firms with which they have a connection or relationship.

However, all businesses need to be profitable to survive, and to do this they cannot exist in a vacuum. Even with the ‘independent’ badge, advisers are not self-sufficient. To be able to act in the best interests of the client, they must navigate a range of relationships — with product providers, platforms and technology suppliers.

Other relationships — with networks, support services or external investors — may also be a necessity for some firms.

“Every good adviser strives to treat clients with an open mind, prioritise their needs and deliver bespoke solutions,” says Danielle Slater, director of IFA firm Stephen Eve Financial Planning.

True independence doesn’t exist — we don’t do this for free

“However, it would be naive to claim that recommendations were entirely free from unconscious bias, stemming from factors such as relationships with fund managers or societal influences, which can impact the true independence of the advice process.”

So, can financial advice ever be genuinely independent?

Defining independence

Advisers who remember the advice industry in the early 1980s tend to refer to it as ‘the Wild West’.

One of the problems — outlined by Jimmy Hinchliffe in ‘The Financial Services Act: a case study in regulatory capture’, a thesis submitted to Sheffield Hallam University in 1999 — was that clients often had no idea if the adviser was acting in their ‘best interests’ independently, or if they were selling products for an insurance firm or bank. As a result, clients were left in the dark about any potential conflicts of interest or bias.

Today’s market is enormous. It’s impossible for any adviser to look at what is available from scratch for every client

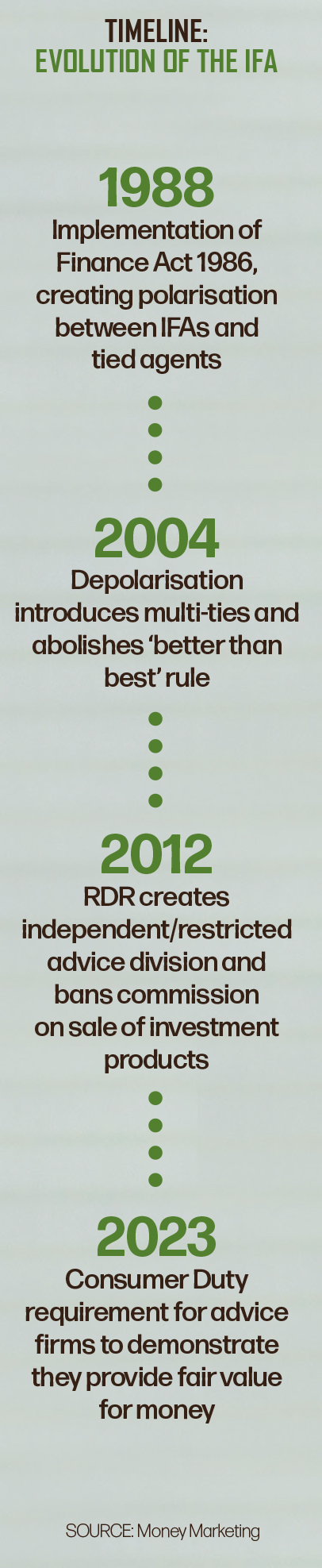

Independent advice in the regulatory sense came into being through the Financial Services Act 1986. The act established a polarised regime, whereby financial advisers had to disclose to clients whether they were either an independent ‘whole of market’ adviser or a tied adviser recommending the products of one company.

This regime was replaced by ‘depolarisation’ in 2004, which permitted advisers to form multi-tied arrangements with product providers. Then, in 2012, the Retail Distribution Review (RDR) created the current definitions of independent and restricted advice.

The regulatory definition of independence still boils down to an adviser’s approach to research and recommending investment products. But some commentators question the relevance of this given that the advice sector has moved away from product sales towards holistic financial planning.

Does being ‘whole of market’ carry as much clout as it used to, bearing in mind that it was established in response to problems that existed in the market decades ago?

IFAs are able to recommend niche products to clients with particular needs, observes FTRC founder Ian McKenna.

It’s about looking not at the clients going into the main platform or proposition but at how the firm handles exceptions to the rule

“But how many clients need all those products all the time?” he asks.

McKenna says advisers used to have to sell products, but now it can be “legitimate, viable and appropriate” to tell clients to do nothing with their portfolio.

“Is the right decision for the financial advice industry something that was created 40 years ago?” asks McKenna. “The industry has moved on so far — it’s now a profession.”

Other commentators think being whole of market is not as relevant as it used to be, but they still regard it as a hallmark of independence because it provides clients with the greatest choice and flexibility.

However, independence is not just about the regulatory requirements — many advisers have their own ‘common sense’ interpretation of what genuine independence means.

Conflicts of interest

Retired IFA Dave Robinson believes that advisers can achieve true independence by being free from influence and conflicts of interest. However, he does not think it is feasible to be independent in the regulatory sense.

I’d like to ask the people at the FCA if they have engaged an adviser and been through the formal advice process

“In 1986, it was possible to be whole of market for most clients as the market was so much smaller,” says Robinson. “Now, it’s enormous and it’s impossible for any adviser to look at what is available from scratch for every client who walks through the door.

“So, every adviser has to put together some sort of proposition. But that proposition has got to be your own thoughts and ideas — not influenced by anyone else.”

Rather than try to research the entire market for every client, many advice firms have a centralised investment proposition (CIP) in place. This focuses on a range of providers and products that suit their client base and should be regularly reviewed.

Although both practical and a vehicle through which consistent advice can be offered, could a CIP compromise an advice firm’s claim to be genuinely independent?

“A lot of people with CIPs and panels would still call themselves independent because they have done the work and pulled it all together,” says Angus MacNee, chief executive of IFA network ValidPath.

The closer the decision makers are to the client, the easier it becomes to be genuinely independent

“That may be true, but it can introduce a conflict of interest.”

MacNee says advice firms can be genuinely independent if they have a CIP, but it depends on whether that would be the only option for clients or if other solutions could be used where research indicated they were more appropriate. Put another way, it is how advisers deal with clients going ‘off panel’ that really counts when it comes to independence.

“It’s about looking not at the clients going into the main platform or proposition but at how the firm handles exceptions to the rule,” says The Lang Cat consulting director Mike Barrett.

“The danger is that independent advice firms fall into the trap of using the same platform and same CIP for all clients, which restricts you around them. In that case, client segmentation and due diligence are not robust.”

‘Independence’ can mean different things to people. As a result, its interpretation has become a bit muddied in the advice world, believes MacNee.

It is fair to charge a percentage fee for complex cases as long as the fee is transparent

“Being independent means the adviser has every tool in the toolbox and is seeking only to support what’s in the client’s best interests, with no commercial gain one way or another in the solutions they provide,” he says. “But not all people who say they are independent are independent.”

MacNee says advisers may make an increased margin if a client uses a certain platform or solution.

“How they are incentivised could create a conflict of interest that rubs up against authentic independence,” he adds.

For wealth management firm Five Wealth, genuine independence is about ‘independence of mind and spirit’ — genuinely servicing clients without any conflicts of interest.

“We are an owner-managed business and we have no external influences,” says the firm’s associate director, Liz Schulz.

“We can challenge the product providers to do better and not feel compromised.”

If clients’ requirements are the same, why should some pay more than others?

Ownership

During the polarised regime, an IFA could not place business with a provider that owned more than 10% of that advice firm unless they could demonstrate it was the best product in the market.

This ‘better than best’ rule was abolished under depolarisation in 2004 because it was felt to be anti-competitive and restricting advice firms’ access to investment capital.

Instead, IFAs were required to tell consumers about any financial ties they had with providers. Sales targets, or other incentives to encourage advisers to do business with the provider that owned them, were also banned.

How an adviser is incentivised could create a conflict of interest that rubs up against authentic independence

The FCA Handbook makes it clear that being owned by a product provider, wholly or partially, is not a barrier to a firm providing independent advice now, as long as the firm is not limited to that provider’s products, looks elsewhere in the market and is not biased. However, Robinson cannot square this with genuine independence.

“I think it’s complete nonsense that a firm of financial advisers that is wholly owned by an insurance company or investment manager can describe itself as independent,” he says.

When he was advising, Robinson had a client whose previous adviser had been part of a firm that was owned by a provider. The client had been invested with that provider in investments that Robinson felt were unsuitable.

However, other commentators say there will be times when the products provided by a firm that invests in or owns an IFA business are the best fit for the client.

A lot of people with CIPs and panels would still call themselves independent because they have done the work and pulled it all together

“There’s no issue with using in-house solutions as long as you can show you are meeting the client’s requirements,” says Morningstar Wealth head of distribution Ben Lester.

“I would have concerns if the majority of customers were going into them. But, if there’s a good split across third-party solutions, that would suggest the adviser has done their job and researched the market.”

Vision Independent Financial Planning is an IFA network that is a wholly owned subsidiary of asset-management firm Rathbones Group. Speaking to Money Marketing, Vision chief executive Zoe King says the network’s ownership structure does not compromise the independence of the IFAs, who are both appointed representatives (ARs) of Vision and limited companies in their own right.

“The AR firms contractually own their client relationships and can leave the network, taking those client relationships with them,” she says.

The industry has moved on so far — it’s now a profession

“If Vision were to even attempt to influence where an AR firm placed business — outside suitability, any restrictions on regulated permissions or our proposition governance standards for the Consumer Duty — we would expect significant objections by those firms, given how fiercely they wish to protect their independence, as well as their ability to win new business on their own merit.

“Why would we want to lose them to a competitor?”

The problem with fees

An area that is becoming a battleground for independent and restricted advisers alike is fee structures.

Prior to the RDR, it was commission that was seen to be undermining independence, due to concerns that advisers were selecting investment products that would pay them the most. Since the RDR, however, advisers have charged fees, but some say there is a conflict of interest when charging clients a percentage of assets under management.

There’s no issue with using in-house solutions as long as you can show you are meeting the client’s requirements

Can advisers say they are genuinely independent if they will earn more money from a client investing — and staying invested — rather than doing something else with their money? Should investors with a bigger portfolio be charged more than someone with less money, even if the work required is similar?

“We all think we act with integrity and independence, but the reality is that in some cases we may not always note conflicts of interest or challenge ourselves on those conflicts of interest,” says Smith & Wardle Financial Planning partner Helena Wardle.

In 2018, Wardle did a master’s degree in financial planning, during which she explored fees.

“I’ve always been intrigued by fees as I couldn’t understand the fairness of charging based on assets under management,” she says.

“If clients’ requirements are the same, why should some pay more than others?”

Wardle runs two businesses and both steer clear of percentage charging. Smith & Wardle charges fixed fees and the other business — Money Means — is a digital advice service that is paid for by a subscription.

Being independent means the adviser has every tool in the toolbox and is seeking only to support what’s in the client’s best interests

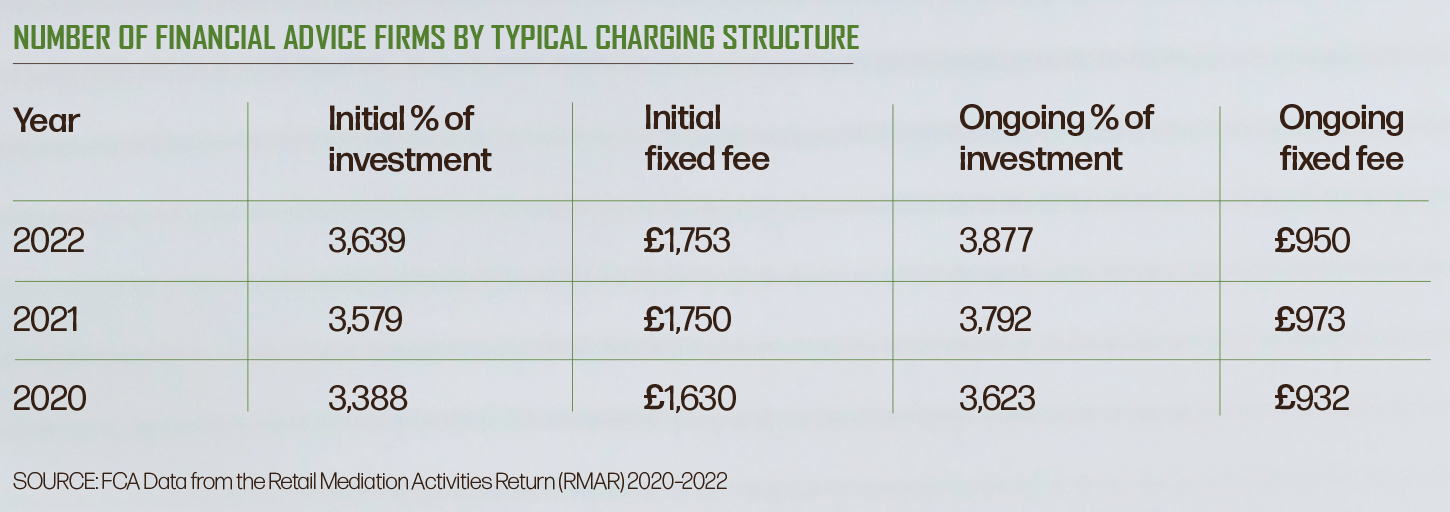

Data from the Financial Conduct Authority’s Retail Mediation Activities return shows that, in 2022, 3,639 financial advice firms charged an initial percentage-based fee and 3,877 firms charged an ongoing percentage-based fee.

In contrast, just 1,753 firms charged initial fixed fees and 950 firms charged ongoing fixed fees.

“One of our biggest challenges is that clients are not spending enough,” says Wardle.

“So, we encourage them to think about whether they want to gift money to their family now and see them enjoy it, rather than wait until they’re dead. There’s no conflict of interest for us to keep it under management.”

Wardle is extremely concerned about what happens to clients who are charged percentage fees when they have made withdrawals from their pension pots and those pots fall below the adviser’s minimum for taking on clients.

“I’ve seen many examples of clients being sent letters of disengagement from advisers who were happy to take the creamy profits,” she says. “Charging based on assets under management is a huge conflict of interest.”

The danger is that independent advice firms fall into the trap of using the same platform and same CIP for all clients

Robinson — who always charged fixed fees on a time-costed basis when advising — agrees.

“I’m 100% sure I’ve seen percentage-based fees encourage people to invest more than they should have done and in an inappropriate risk profile,” he says. “The rationale for this is higher-risk investments will go up more and the adviser gets paid more.”

When advising, Robinson was asked to give a second opinion on a case where an adviser had recommended equity release rather than drawing from investments.

“There can be situations where that is appropriate — but in this case it was sensible to draw from the investment,” he says. “But, if a client makes withdrawals from their investments, it will affect the adviser’s ongoing fees.”

IFA firm FPC offers clients a fixed-fee option.

FPC managing partner Moira O’Shaughnessy says: “This is priced on how long the work is going to take us. We can rarely cover our costs, but we don’t want this to be a barrier.”

Every adviser has to put together some sort of proposition. But that proposition has got to be your own thoughts and ideas — not influenced by anyone else

O’Shaughnessy thinks it is fair to charge a percentage fee for complex cases as long as the fee is transparent.

“That is where the Consumer Duty comes in: how can you evidence that you add value? It forces you to look at your charges to see where you add value.”

Does size matter?

Some advice firms, especially small ones, join a network for help with regulatory and compliance requirements. There are plenty of positive experiences of how networks can help advisers maintain their independence.

Schulz, for example, says: “We’re part of the Sense network and I think it’s a good way to build our business. They require us to justify every decision we make, which is an extra level of compliance.”

Susan Hill Financial Planning director Susan Hill agrees.

“Their compliance enforces what the FCA asks us to do — that’s why I stay with a network,” she says.

However, Hill’s previous experiences show that not all networks are equal. While some are fully supportive of IFAs, others seem controlling and restrictive.

It would be naive to claim that recommendations were entirely free from unconscious bias

Hill sets an initial flat fee and a percentage-based ongoing fee. Many of her clients are women, some of whom are divorced and do not have much money, but a previous network would not permit her to charge a flat fee for some clients.

“They pander to the FCA and the Consumer Duty, but they haven’t worked out what’s happening at the coalface,” she says.

According to Hill, the problem arises because the senior staff of a network — and even the regulator — have always managed their own money and have never been to see an IFA in a personal capacity.

“I’d like to ask the people at the FCA if they have engaged an adviser and been through the formal advice process,” she says.

Some commentators point out that small firms make up the majority of the IFA market, with many comprising one-person firms. Given that it costs more to run an IFA firm than to run a restricted firm, it is easy to assume that it is harder for small firms to be independent. However, Barrett has a different perspective.

Is the right decision for the financial advice industry something that was created 40 years ago?

“The closer the decision makers are to the client, the easier it becomes to be genuinely independent,” he says. “If the person giving advice is also making decisions on how the business is run, it’s easier to say, ‘This client needs something a bit bespoke,’ rather than ring head office and be told they’re restricted.”

However, for some advisers, true independence is a pipe dream.

“True independence doesn’t exist — we don’t do this for free,” says Wardle. “We just have to acknowledge our conflicts of interest and manage them.”

This article featured in the June 2024 edition of Money Marketing.

If you would like to subscribe to the monthly magazine, please click here.

True Independence, means completly unbised, and absolutly no third party inducement, inflewance or financal reciprocation. We are here and I refute we can not be. Our only income is derived directly from and with the clients agreement.

Good for you Robert! I know I was not alone. Indeed another facet of independence is having the capacity for refusing business. The word ‘no’ features all too rarely in the advisers lexicon.

Well Amanda, I never realised you were part of SJP’s PR department! Without writing a complete essay in response I would just make a few salient points without rambling on too long.

The whole article presumed that products are front and centre. I always used to say that the product (if there was one) is free, it is the advice that is paid for – whether or not a product is purchased. Not infrequently a financial solution does not need a ‘product’. One of the most important criteria for independence is whether the adviser can fix their own tariff and explain clearly on what it is based. (Not on FUM). As your article correctly pointed out; that when it comes to products an independent should select from a suitable diverse range of relevant products. This doesn’t mean and never has that every single available item has to be considered. In house items are a non sequitur as far as many independent (and often smaller) advisers are concerned. They just don’t have in house products. When it comes to investments (and that includes pensions – which are just investments with knobs on) the only prejudice is profit. What is undoubtedly bias is all this ESG and Woke. If these don’t detract from the potential for profit then well and good, but to be unbiased should they really be the initial issue?

When it comes to life assurance this is where the regulations fall down. Commission is still permitted, so a true independent will charge a fee for the advice instead. How justifiable is it for a £750k sum assured to pay more that for a £500k sum assured? Anyway, when a little arithmetic is employed, the client should be able to see how much better off they would be with a fee rather than commission.

How you can even mention independence and a network in the same sentence is beyond me.

Finally, to aid objectivity it is a good idea for the adviser to have ‘skin in the game’. Too few fill this criterion.

There is certainly such a thing as true independence. A good few actually practice it, as did I. It is still the gold standard and clients need to be aware of the differences and advantages.

Isn’t it time that this article was consigned to history. It seems to be a permanent fixture on the site.